Project Description

Project Description

Streetworks: Inside Outside Yokohama

Curator: DAVID BROKER

In Australia’s contemporary art scene Craig Walsh and Shaun Gladwell might be described as phenomena. Working from a relatively new country where the only uninterrupted cultural traditions are Aboriginal and the majority of the population’s cultural history comes from elsewhere, both have developed considerable international reputations. This is despite the global art market being so geographically distant. While on many levels their practices might have little in common there is one significant similarity: both utilise the streets or generic urban space as the milieu in which much of their work is generated. Arguably it is this aspect of their respective oeuvres that has enabled audiences far beyond Australia to enthusiastically embrace their work.

While conventional art galleries from national institutions to modest art spaces remain important exhibition venues for Gladwell and Walsh, for both, institutions of this nature have a certain irrelevance. Over a period of many years Walsh has produced work in abandoned buildings, car parks, alleys, shops and railway stations determinedly taking his work to a section of the public that, by and large, might have little interest in the heady domains of high culture. He has also conceived of effective ways of bringing gallery audiences together with people at the theatre, rock concerts or just simply wandering along some well-worn urban pathway. Similarly, Gladwell’s video work seems to stand astride the extremities of specific audiences. His documentation of popular subcultural activities such as skate boarding, break dancing or BMX biking in familiar metropolitan settings are much more than a screen-based representation of diversionary youth activities: Gladwell’s distinctive eye transforms everyday pursuits in the most ordinary environments into extended moments of sublime beauty, thereby seducing audiences.

This exhibition began in the streets of Yokohama, Japan. In retrospect it makes perfect sense that the curators of the Yokohama 2005 International Triennale of Contemporary Art would select Walsh and Gladwell as Australia’s representatives and commission both to produce works over a period of four weeks leading up to the opening. Subtitled Art Circus (Jumping from the Ordinary) the Triennale focused on work that presented commonplace activity in a way that made the most mundane of moments exceptional and at times even strange. Here were some 85 artists from every corner of the globe who made convincing arguments that there was more to everyday life than meets the eye. In Walsh’s works routine public activities in the context of an art work become noteworthy. The reverse is true of Gladwell’s subjects who are seen in flamboyant acts of performance and yet these youthful protagonists are also simply going about their daily business.

Working in a Japanese city, doing what they might do in Australia, it quickly became clear that the work of both artists was not culture specific and herein lies the secret of their accessibility. Where it might be necessary for many artists to develop an audience, Gladwell and Walsh, in different ways, have ensured that audience is central to and part of the finished product. Through this heightened form of documentary we see ourselves both as we are and as we might be, commonplace and exceptional.

With a career approaching 15 years, Craig Walsh’s work has nearly always included a public component, even when the work was part of a gallery program. From the early 1990s Walsh has worked primarily with ephemeral public installations and a significant part of his work existed only in documentation. In the Self Promotion tour (1997), he explored the difficulties of working in this way by sending two containers of information about his practice to galleries throughout Australia. At Brisbane’s Institute of Modern Art, Adelaide’s Experimental Art Foundation, Sydney’s Artspace and Mebourne’s Grand Central Art his work often occupied street front windows, a zone between the gallery and the street. Also in that year, Walsh produced a work that transplanted the tradition of the framed wall work into a space used by a very transitory public. The Brunswick Street Collection (1997), consisting of several large framed mirrors suspended on the crash wall of the Brunswick Street railway station in Brisbane, reflected commuters on the platform. This work effectively incorporated the audience as a primary component, while actively engaging people into a work that also had elements of a fun fair’s hall of mirrors. The notion of audience as medium was extended upon in 1999 with In Perspective at the Queensland Art Gallery where the eyes of people peering into a model of the gallery were projected onto the walls of the same gallery.

Throughout the 90s Walsh also developed a parallel career in the world of music festivals and community cultural events. His projections of human faces onto existing trees became a popular addition to the program of entertainment at the annual Woodford Folk Festival near Brisbane, Queensland, and around six years later these works reached a larger audience at the renowned Womadelaide’s world music festivals in Adelaide, South Australia. Simultaneously his ever-expanding audience included rock music fans at the Livid and Big Day Out festivals in Brisbane, Sydney and Melbourne. At these events Walsh often organised visual arts programs suited to the festival atmosphere, providing artists with opportunities to show work to large captive audiences a long way from the mausoleum-like environment of traditional museums. For the Adelaide Biennial of Australian Art during the Adelaide Festival of Art 2004, Walsh merged these two elements of his professional life with two distinct audiences for a work titled Cross-Reference. At the Art Gallery of South Australia, viewers watched surveillance footage of fans at Sydney’s Big Day Out 2003/04 as they peered into a box containing a model of an art gallery. This footage was back-projected onto a screen suspended in an existing door of the gallery, through this half opened door and set amongst other works on the gallery walls, Walsh created an illusion of engagement between two audiences, locked in mutual observation.

In 2001, on an Asialink residency in Hanoi, Vietnam, Walsh was challenged with the prospect of producing a work for audiences who would not be familiar with either him or his particular practice. Blurring the Boundaries attempted to confuse the distinctions between art and architecture, the natural and built environments, with a projection that created the illusion of a restaurant filling with water. Viewable only from the bustling street, this work amazed its audience as a familiar architectural space took on the properties of an aquarium, complete with fish. In an environment where a public intervention of this nature was unusual, Walsh successfully crossed the cultural barriers that previously defined his practice by manipulating scale and subverting architectural function. In other words transforming a familiar experience for the local Vietnamese audience into something extraordinary.

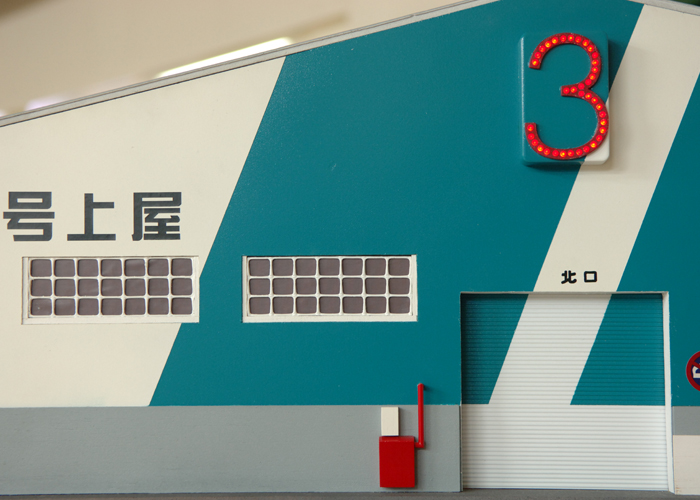

The Yokohama Triennale was housed in two large converted warehouses on Yamashita Pier, part of Yokohama port. The model used in Street works is in fact one of the warehouses and marks a considerable leap in the sophistication of Walsh’s ‘gallery’ models. Built to scale in Australia and transported to Japan, the model was situated in Yamashita Park on Yokohama’s waterfront, an area frequented by tourists and workers seeking a moment of quiet or solitude.

The title Cross-reference, 35:27:02N/139:39:36E refers to the exact location where the work was displayed. The piece attempted to make connections between the original usage of the warehouse and its new role as an art gallery exhibiting works by artists from all over the world. During the exhibition in the warehouse/art gallery audiences saw moving images of people in Yamashita Park peering into the model. These pictures were then back-projected onto screens positioned adjacent to the doors in the gallery giving the impression of a real time connection between people in the two locations. A monitor set between the two entrances shows people in the park walking up to the model and informs the gallery audience of what is happening. With this complex network of interrelated technology Walsh produces the sensation of a complex and multi-layered engagement between exhibition visitors and people on the pier whose involvement in the finished work exists in different times. For those in the gallery this produces a feeling of being watched.

As this work goes on tour, new audiences are able to experience something of the original work as they also connect with an audience in Yokohama. A surveillance camera inside the model records current viewers whose image is projected onto the gallery walls along with footage from Yokohama. Thus the scope of the original work in its two nearby locations becomes a truly international experience.

In Shaun Gladwell’s video works audience is often absent and, when present, somewhat irrelevant. Where there are people they tend to be oblivious to what is happening in their surroundings. Many of his works have employed sterile or barren urban landscapes containing stark architectural forms that provide an environment in which energetic human performance takes place. These are the areas where kids hang out and over the years youth subcultures have gathered in public spaces that are frequented less by adults or authority figures. They are generic metropolitan spaces that are recognisable almost anywhere in the world: unattractive and uninviting with an ambience of risk, while often possessed of a desolate beauty. Empty petrol stations, railway stations, train carriages at night, city streets and department stores are the stage for break dancers, skateboarders and BMX bikers. In Gladwell’s works these spaces are activated by performance and, by way of their neutrality, to some extent appear to activate the performance itself.

Storm Sequence (2000) is arguably Gladwell’s seminal work. In this work we see the artist himself boarding freestyle on the foreshore of Sydney’s iconic Bondi Beach. There is apparently no one on the beach or the streets that day and as we watch Gladwell’s moves, a brewing storm to which he is oblivious, moves in from the turbulent sea. Reminiscent perhaps of the masters of Romanticism who set humanity against an awe-inspiring vision of nature Gladwell is every bit the romantic hero. His solipsistic obliviousness to the storm prioritises the senses over intellect, emotion over reason and whether intended or not, the storm seems to serve as a metaphor for the turmoil of adolescent youth whose diversionary activities can be viewed as a form of release.

Concentrating on the (often extreme) sporting escapades of urban youth, Gladwell describes street skating as a “genre recording architectural forms” that, “presents the greatest point of conflict with security and property owners”. While ‘public space’ may well provide the context for Gladwell’s performers there is always a sense that they should not be there. A hint of illegality or trespass adds to an atmosphere of threat in every work. The artist himself swings on the handles of a train carriage late a night in Tangara (2003), a police car glides past a capoiera (Brazilian martial arts) dancer in an empty Sydney petrol station in Woolloomooloo Night (2004) and in Hiraku Sequences (2001) a BMX biker rides into a fast food restaurant, does a wheelie, then returns to the streets. In Gladwell’s introspective world no one seems to notice. The very notion of public space as it is seen in Gladwell’s videos is challenged and redefined as the questionable appropriateness of location adds to the discomforting excitement of each piece. At this aforementioned ‘point of conflict’ tension develops by way of an awareness that while certain pursuits contravene the designated use of a particular space, importantly, this is also the space where such pursuits gain currency.

The work produced in Yokohama follows certain lines, marked and unmarked, imaginary and real: city thoroughfares. An ultramodern department store provides the mise en scene for Yokohama Untitled (2005) as Gladwell’s camera follows a break dancer along a seemingly endless marble walkway. Accompanied by department store background music and dressed in black baggy trousers, black singlet, black arm band, head band and Adidas sneakers the dancer stops intermittently where he breaks into a series of boisterous and elegant dance steps. Shoppers glide past the dancer in slow motion, as always, seemingly oblivious or just disinterested in the spectacular display of youthful exuberance that is at once impulsive and yet completely controlled. This work is replete with paradox as it focuses on a kind of impetuous transgression that is also highly refined. As the action moves to a railway station notable only for its sterility, one is reminded by the department store that youth culture for all its rebellion is driven by consumerism. Dressed more casually, the second dancer follows a more defined line that is built into the tiled floor. With the control of a gymnast the new protagonist appears to be instructed by the architecture of the space, his performance timeless and open ended, as he follows an ‘infinite’ line that disappears into the distance. Gladwell’s ‘characters’ swagger through the city, using the architecture to benefit their actions, and unperturbed, challenge the rules and conventions of space. In a word, they are cool.

The rumble of wheels on bitumen provides an effective soundtrack for Yokohama Linework (2005) in which Gladwell himself takes to the streets. Ground blurs and roadside objects flash past generating a sense of speed and accentuating the ever present element of risk. His camera trembles as it focuses on the boarder’s sneakers and, ever intent on celebrating skill, Gladwell details the inextricable affiliation between skater, board and street. Following the road markings with considerable determination he subverts their utilitarian purpose in the cause of the game.

In many respects the work of both artists has more in common with cinema than much of the art we see in galleries today. Reminiscent of the French New Wave of the 1950s and 1960s, Gladwell and Walsh have effectively used similar devices to film-makers such as Jean Luc Godard, Claude Charbrol and Françoise Tuffaut who were also noted for their youthful iconoclasm. Free editing (where editing is used at all), long takes, the use of real time, extended time lines and open beginnings and endings, provide audiences with a greater sense of verité or actual experience. It is devices such as these that generate excitement, that open a space where things can happen spontaneously and unexpectedly, and yet it is important to remember that ultimately most audiences will encounter these works in galleries. Audiences will see them and understand them within the context of other paintings, sculptures, photographs and installation. Aware of this reading, Gladwell and Wash produce work that ‘blurs boundaries’, work that is elegantly poised between the artifice of performance and the realities of documentation, popular culture and ‘high’ culture, and of course the gallery and the streets.